Do video games make people violent? I could have ended here with a resounding ‘no’, but it’s in fact a matter of national debate. But let’s go beyond the initial question. Since when have video games been considered violent? Grab your magnificent Disco clothes and your copy of ‘Don’t Go Breaking My Heart’. Rewind to 1976 and the arcade game Death Race.

I lied in fact. Our story actually began in 1975, when Steven Spielberg terrified the world with his film Jaws and 10cc rocked the charts with their hit I’m Not in Love. That year, Californian company Exidy, which specialised in creating arcade games, decided to release a game with an evocative name: Destruction Derby. In case you’re wondering, the game has nothing to do with the project that would be released on PlayStation 20 years later, even though the basic premise and goal are the same: to destroy your opponents’ cars and be the last one standing. The player controls an ugly T-shaped pixel with wheels and must collide with other ugly T-shaped pixels with wheels to eliminate them. However, there is one peculiarity: when the player collides with them, they leave the wrecked cars behind them on the track, making it more difficult to move around the level. The game ends when the time limit expires.

Although Exidy had a good game by the standards of the time, the small company was unable to promote it beyond its own sector. Peter Kaufmann and his partners decided to sell the rights to the game to Chicago Coin, which would distribute the product through its network under a new title: Demolition Derby. But disaster struck when Chicago Coin went into bankruptcy, leaving Exidy legally unable to recover the rights to its game and sell it again, forcing it to reinvent itself.

Credits: Dot Eaters

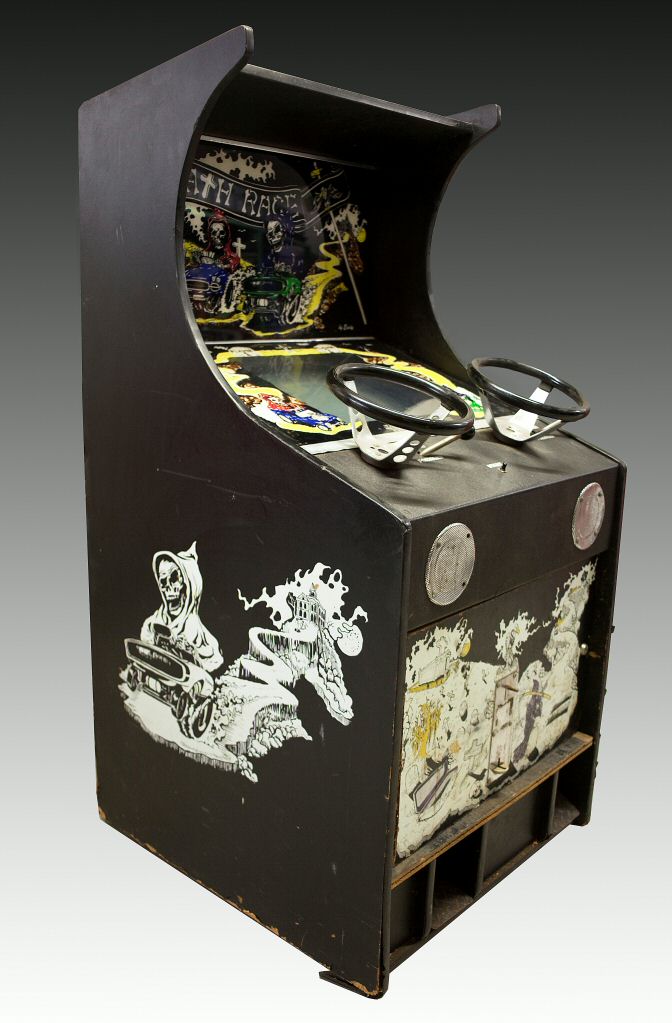

So, what could be better than taking the existing basis of their project and modifying it, replacing the other cars to attack with humanoid figures called ‘Gremlins (no relation with Joe Dante’s movie). From there, the not-yet-controversial Death Race was born. The aim of the game is once again very simple: crush as many ‘Gremlins’ as possible in the shortest time possible. Each enemy crushed leaves behind a TERRIFYING scream and a grave. The more enemies you crush, the more graves there will be on the screen, making it all the more difficult to move around. This is exactly the concept described above for Destruction Derby. Exidy did not want to spend too much time on this project, which was considered an interim game to tide players over until Car Polo (the Rocket League of its day!) was released in 1977.

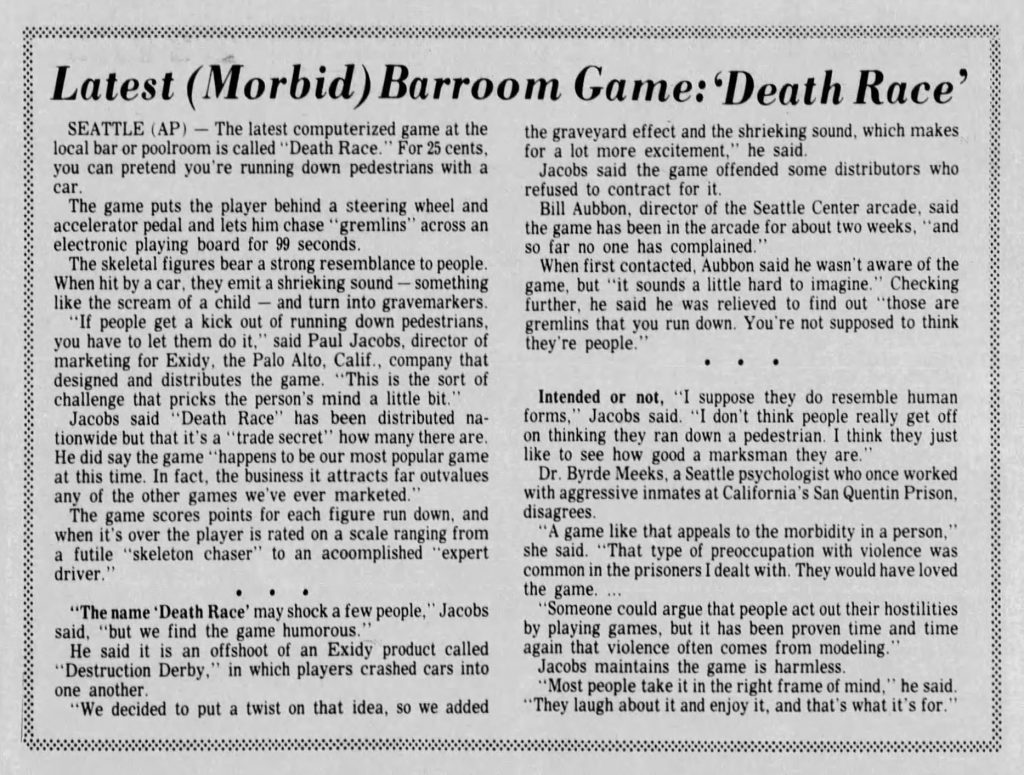

Although the game’s release in April 1976 did not cause much of a stir, things began to heat up three months later when journalist Wendy Walker wrote a concerned article about the title in July 1976 for the Ithaca Journal, which had the effect of a powder keg. According to her, the characters that players run over resemble pedestrians. From there, various media outlets, mainly local ones, picked up on the story, albeit in a truncated form (because otherwise, it wouldn’t sell). But the bomb really exploded in December 1976 when the National Safety Council also published an article, triggering a second wave of outrage. And they didn’t mince their words, starting with a summary of road accident statistics before unleashing their wrath with the famous line, ‘Death Race is not a video game!’ Holy Cow. This time, the story was picked up by national media and broadcasters, who immediately resorted to the tired old clichés of a good old-fashioned attack on video games : disturbing music, damning testimonials, experts invited who are more or less committed to the cause they are asked to criticise. And even distortion of the subject, for example by referring to ‘children’s cries’ when running over pedestrians. Petitions were signed, politicians took up the cause, and even developers from the era, such as Nolan Bushnell, one of the co-founders of Atari, became critics of this violent game.

The game would go and be analyzed from every angle. First of all, its name seems very similar, too similar to Death Race 2000 , a film released in 1975 by Roger Corman set in a dystopian America, where drivers must run over participants to score points in order to win. The developers dismissed this as a mere coincidence. Then the arcade cabinet designs by Pat “Sleepy” Peak, featuring a skull, attracted further suspicion. Later, it was even said that the game’s code name was supposed to be “Pedestrian.” This was another way for detractors to demonstrate the link between the violence of the title and the twisted minds of the developers. This information was denied by the creators themselves, and its origin remains unclear.

Then, two years later, no one was talking about it anymore. Like a collective amnesia, the title fell back into the anonymity it had known at the time. But bad press is always good for business. And thanks to this affair, Exidy managed to make Death Race one of the most profitable arcade games of 1976, although none of the developers know the exact number of machines installed. All we know is that it was reissued at least three times, with estimated sales of between 2,000 (the most likely figure) and 6,500 units. Of these, approximately 1,000 to 3,000 units were sold after the controversy. A spiritual sequel called Super Death Chase was even considered at one point, but it seems it never saw the light of day. However, the most beneficial effect was not so much on Death Race as on Exidy itself, which managed to make a name for itself nationally, to the point where it was able to compete with the industry leaders. It even managed to survive the video game crisis of 1983, before disappearing in 1999.

Death Race is therefore the first well-documented example of society’s mistrust of video games. And while there would be even more extraordinary examples in the future, notably the memorable Mortal Kombat lawsuit (which deserves a movie of its own, as it represents the height of the rivalry between Sega and Nintendo in the mid-1990s), this skepticism became firmly entrenched with the precedent set by Exidy’s game. For example, without questioning its relationship to violence this time, Nintendo itself went through a turbulent period in the late 1980s as it attempted to definitively establish itself in the American market with its Super Nintendo. Once again, parents and the press questioned the dangers and addictiveness of video games, and a new word was even invented during this brief period: Nintenpendancy. All this to conclude that controversy and video games seem to go hand in hand. Whether a video game is violent or offers something different from others. When will it end? One day. Only time will tell.

For more information :

https://gamehistory.org/media-vs-death-race

https://allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com/2012/12/death-race.html