The year is 1991. The Super Famicom (the Japanese SNES) has been out for almost a year, the Megadrive (or the Genesis in North America) for three years, and the new decade is moving towards increasingly sophisticated games, all dreaming in 3D. Yet it was during this promising but unstable period that the most intriguing space opera of the previous generation took off. Between failure and palace revolution, let’s join its creator, who has done us the honour of answering our questions, as we discover the greatest unknown in the Famicom catalogue: Metal Slader Glory.

Departure

Let’s rewind to 1978. Every week, a group of friends meets at the Seibu store in Tokyo’s Ikebukuro district to talk about computers, discuss the latest microcomputers on sale, or test their prototypes on the machines. Arcades were on the cusp of their first golden age, while Nintendo had just entered the console market with its Color TV Game range. Among these enthusiasts was a brilliant academic and genius programmer. At the time, there was no indication that the young Satoru Iwata would become one of the most iconic figures in what was then a prehistoric video game industry. Satoru was not just a fan who visited the shop. He also worked there part-time under Mitsuhiro Ikeda, who was just starting to develop plans for a small company.

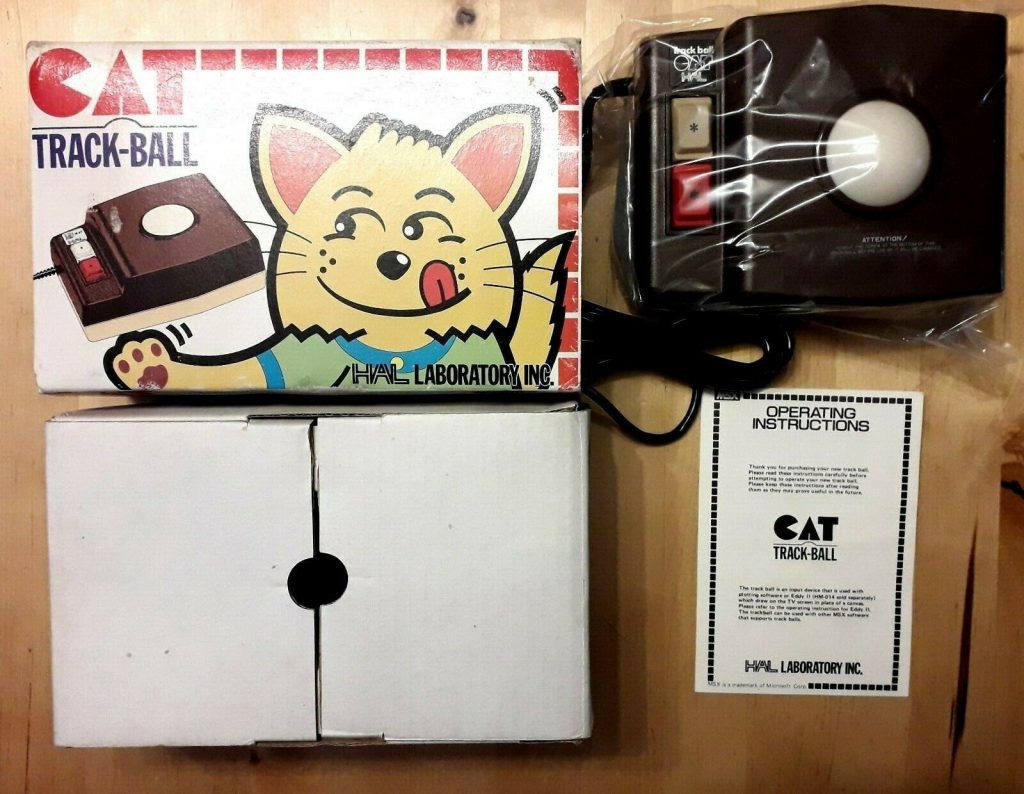

Although HAL Laboratory is now inextricably linked to Nintendo, particularly through its iconic character Kirby, the company specialised in its early days between 1980 and 1982 in creating various peripherals. These included the incredible PCG chip, which improved the graphics and sound capabilities of Commodore microcomputers, and unlicensed Namco game clones. However, it was Namco itself that contacted them in 1982 to design games for them. Buoyed by relative success, the small firm of five people, working together in an apartment, moved to larger premises with revised ambitions. And they had no shortage of them.

in the early days of Hal Laboratory (Issue 0 of MSX Magazine)

Now a young professional working in HAL’s development division, Satoru Iwata saw with seasoned eyes the revolution that was about to shake Japan on the 15th of July 1983. In quick succession, the Sega SG1000, which would become the Master System in the West, was released, but more importantly, the Nintendo Famicom, which would transcend video games and whose significance he immediately recognised. With his clear vision, it was precisely with Nintendo that he attempted to forge a working relationship in his twenties. Luckily for him and HAL, one of their financial partners was good friends with Big N, which facilitated the formation of a formal alliance that benefited both parties.

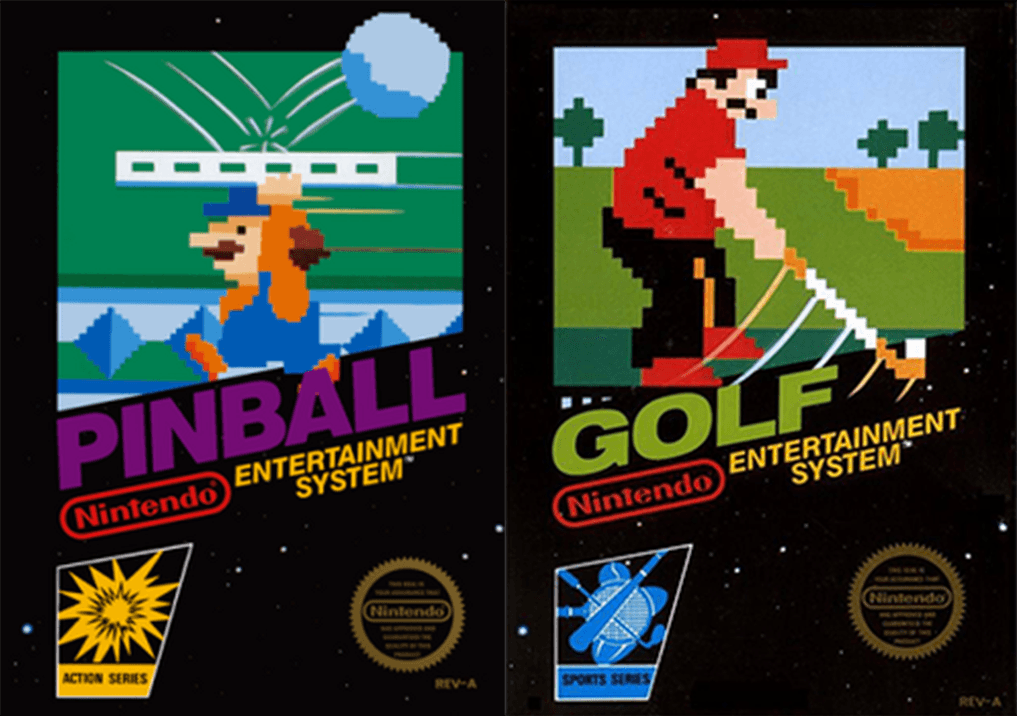

Although HAL’s first game in 1983, a port of the arcade game Joust, was cancelled due to copyright issues, they quickly found themselves working on two other games, Golf and Pinball. And since the Famicom’s microprocessor was exactly the same as the one that had been in his Commodore Pet six years earlier when he was in college, Satoru Iwata let his genius shine through by implementing an 18-hole course in Golf when everyone thought it was impossible, and by coding one of the best physics systems ever seen in a pinball game into Pinball. The latter would later be reused in numerous titles, both Nintendo and non-Nintendo. The work done on Joust would also not be in vain, as the game’s physics would be recycled in another iconic Famicom title, Balloon Fight, in 1984. The Nintendo/HAL Laboratory duo became inseparable from a period when Mario and Zelda had not even been released yet.

It was also in the midst of the turmoil of 1984 that HAL changed its presidency, with Mitsuhiro Ikeda stepping down and Tsuyoshi Ikeda taking his place in a company undergoing major changes. Between then and the early 1990s, the company grew from 5 to 90 employees and established a presence in the United States, while continuing to produce a variety of titles. While Nintendo remained its preferred partner (Iwata even occasionally helped out with the programming of certain titles), HAL collaborated with Sony on its MSX microcomputer, as well as on associated peripherals such as the HALFAX-9600, a fax machine that could be connected between the MSX and a printer (which has since disappeared). In terms of games, this period saw the release of the puzzle/thinking game series Adventure of Lolo, as well as the beginnings of a series inseparable from the duo, Mother. Other more obscure curiosities were also produced, such as the one that interests us in particular.

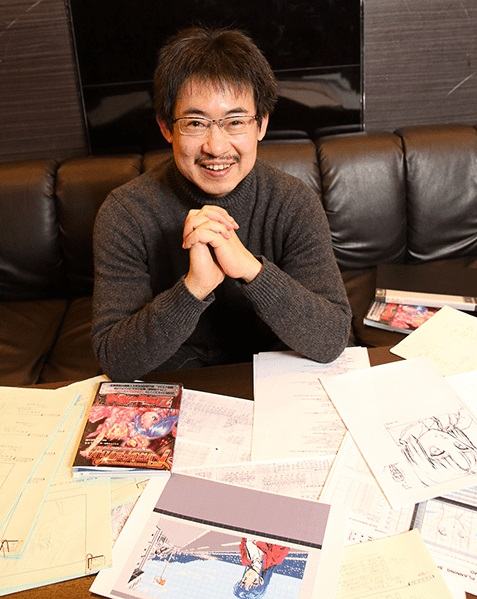

Look into the future

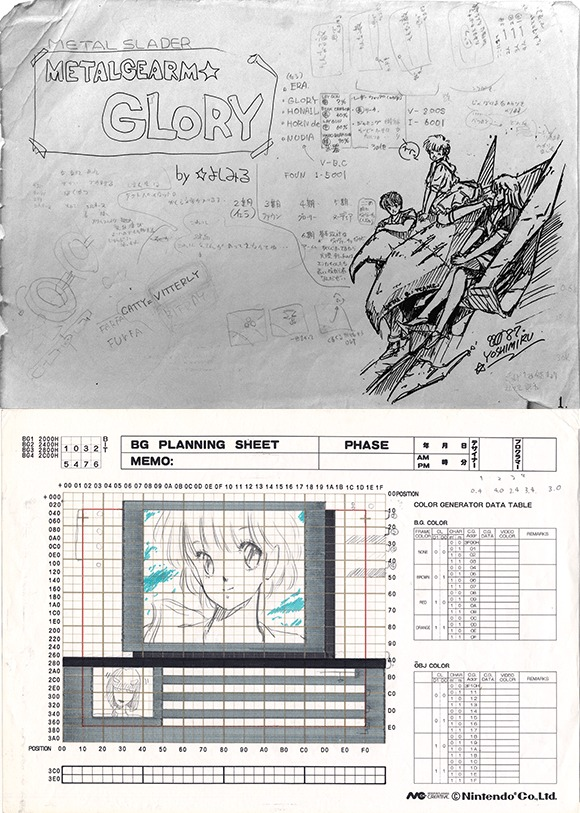

As engineering technicians, HAL developers lack creative initiative at the time. A major internal project is therefore being set up to enable the teams’ ideas to come to fruition, even for freelance contracts. Yoshimiru Hoshi seized this opportunity to pursue a spin-off from his aborted first manga creation. Before working in video games, Yoshimiru was a mangaka, illustrator and Gunpla model maker for three magazines: Fan Road, then Work House and Hobby Boy. These considerations were important and motivated his major project, which he diligently prepared for a formal presentation. It was then that Iwata, then head of development project management at HAL, happened to drop by his office and was captivated by what he saw. Without any presentation, based on a mock-up, a vague design document and a few animations, Hoshi’s project was approved.

But what on earth possessed Satoru Iwata to give the green light to a project he hadn’t even seen? The answer lies in a term that could be applied to modern video games: production. Indeed, the project was artistically impressive. Iwata didn’t confide this to Yoshimiru until several years later, but the aesthetic promise of the title surpassed anything that could be done on the Famicom at the time. No one had ever seen such refined and detailed graphics on the console before. And perhaps no one will ever see such detailed graphics again. But Iwata was not fooled, and he still wanted to test Hoshi’s claim, who agreed to be paid only through royalties upon the game’s release. A development team was then assembled and, in 1987, the project named Metal Slader Glory, a science fiction visual novel, largely designed by Yoshimiru, took off towards a completely unknown horizon.

Frontiers

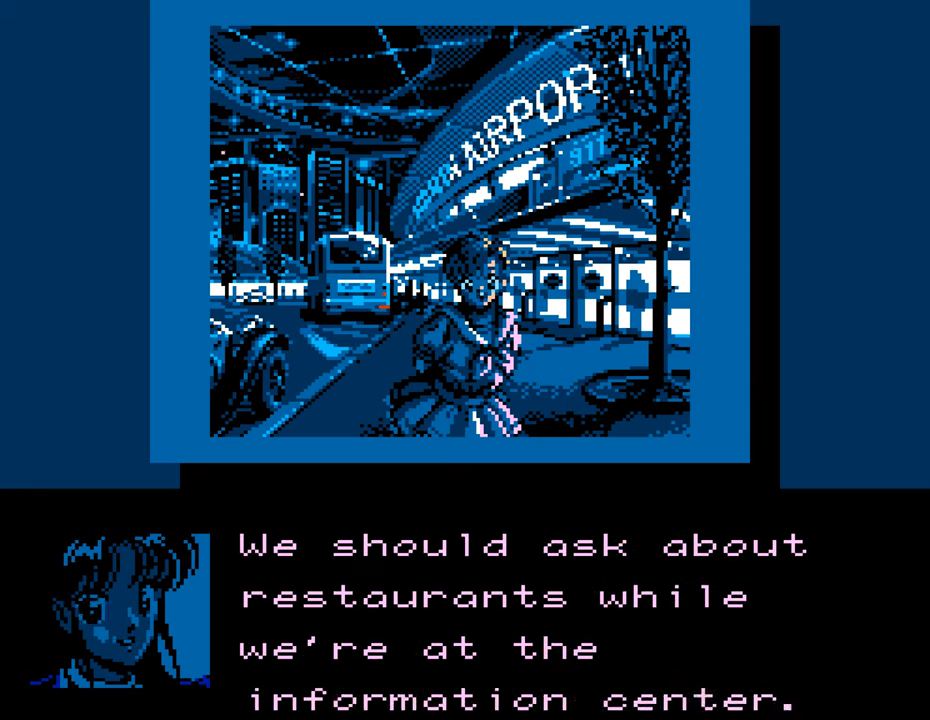

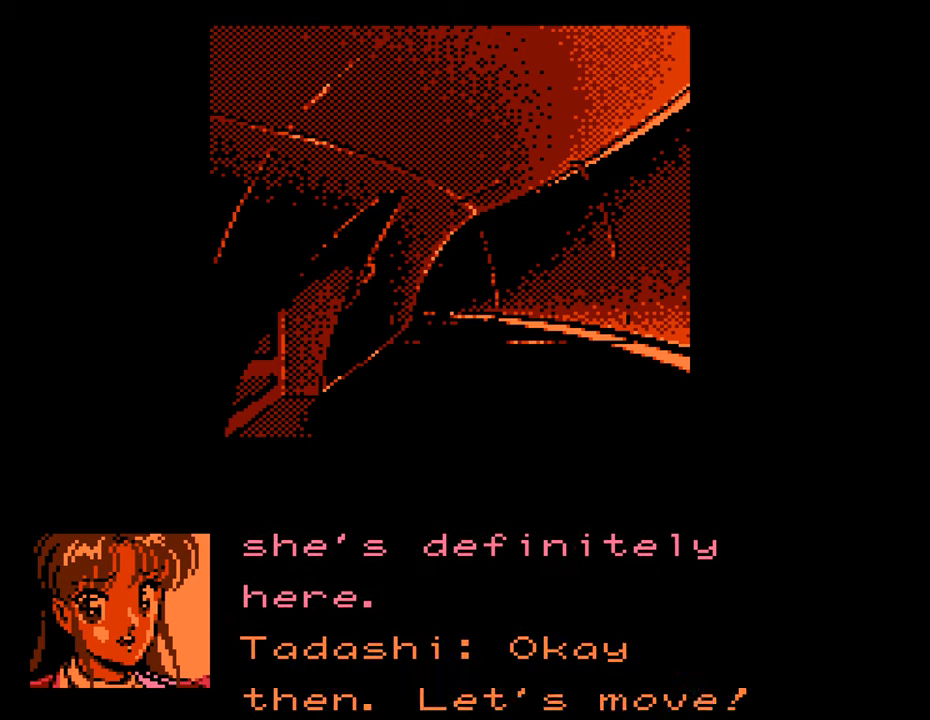

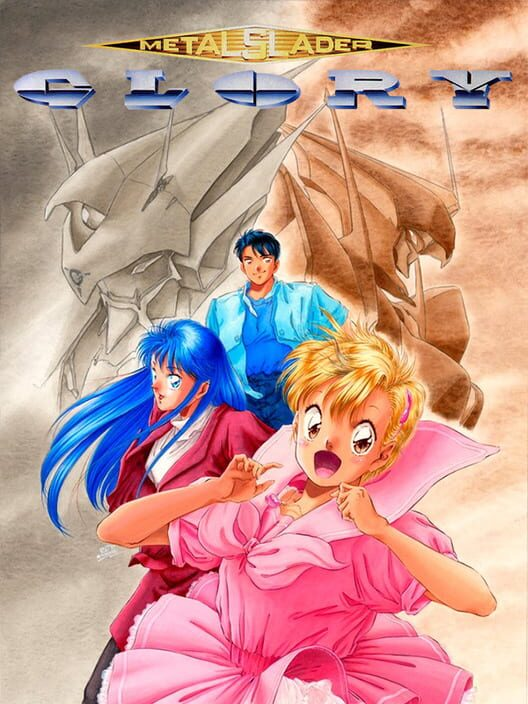

Taking off into the unknown is also the destiny of our three young protagonists in the year 2062: Tadashi, his little sister Azusa, and his girlfriend Elina. Together, they embark on a space epic with the goal of determining who owned a robotic operator that Tadashi woke up in an old scrapyard. Only its name provides a clue to the investigation: ‘Metal Slader’, a very special Mecha model used in the space war eight years earlier. Thus begins our adventure, even though the basis for it is recorded in about twenty pages of a manga written by Yoshimiru himself, which can be found in the preamble to the user manual. However, it is not necessary to consult it to fully enjoy the adventure.

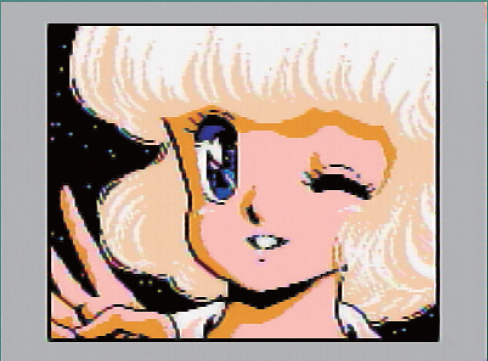

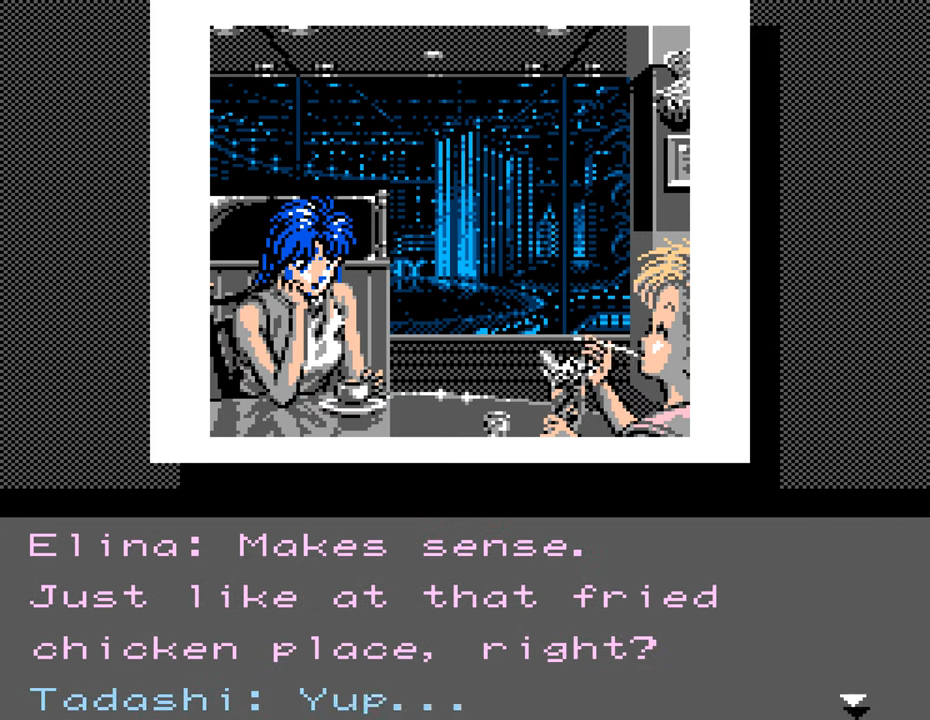

The first thing that strikes you when the game opens up into the vastness of space (perhaps one of the most impressive openings in an 8-bit game) is the beauty of the graphics. Satoru Iwata was right, and Yoshimiru’s team rose to the challenge brilliantly: the game is magnificent. From the highly detailed backgrounds to the evolving facial animations during dialogues and the fluidity of the shots, everything comes to life in a multitude of details that play on, or even circumvent, the technical limitations of the Famicom in terms of colours and sizes. And while, as mentioned above, Metal Slader Glory is a visual novel with limited interactions, you will very quickly be able to navigate between different areas of a space station, then between several planets, each location offering its own atmosphere and expressions.

Although it does not appear to be revolutionary in these respects, dealing with the clichés of the genre, such as having to emphasise a specific point to move the story forward, the game channels its pace admirably, politely avoiding the trap of lengthy exchanges between the various protagonists. The chemistry between the three main characters also works very well, even if Azusa, due to her youth in the adventure, is a little behind the other two. The result is an express fable that, in five hours, reveals and summarises all its issues. Paradoxically, however, the game takes its time, allowing for a conversation over coffee, or cleverly dressing up its password system (no saving in the strict sense here) with a subtle invitation to take a nap.

With a certain tranquillity and fascination for the universe it offers us, Metal Slader Glory ultimately tips over into great anxiety and absolute urgency. Here again, the title surprises with the coherence of its narrative line, even allowing itself a few original touches. Yoshimiru confided to me in our brief exchange that he had been influenced by various titles that he sometimes used counter-intuitively in his own productions, such as Jesus: Kyoufu no Bio Monster, whose references are obvious. And in this respect, the journey through the recursive colony 3 is an extraordinary moment in itself. With its dark setting and heavy music, it is in fact a very simplistic but highly immersive horror dungeon RPG in which you must find Azusa, who was kidnapped some time earlier, while watching out for alien attacks that can occur at any moment.

☆よしみる : 色々なアドベンチャーゲームをプレイしました。

その頃の他のアドベンチャーゲームの内容はグラフィックも単純で、シナリオ自由度

も低かったので、

違うものを作りたいと考えました。

影響されたという訳ではありませんが『英語版ブレードランナー』『スナッチャー』

『ジーザス』等をプレイしました。

特に『スナッチャー』『ジーザス』は私の思う理想のアドベンチャーゲームではな

かったため、反面教師的な意味で

参考にしました。

Yoshimiru Hoshi : « I played various adventure games.

At the time, other adventure games had simple graphics and offered little freedom in terms of the storyline.

So I wanted to create something different. »

« I wouldn’t say that these titles influenced me, but I did play Blade Runner (English version), Snatcher and Jesus.

Snatcher and Jesus didn’t match my ideal of what an adventure game should be,

so I used them as counter-examples. »

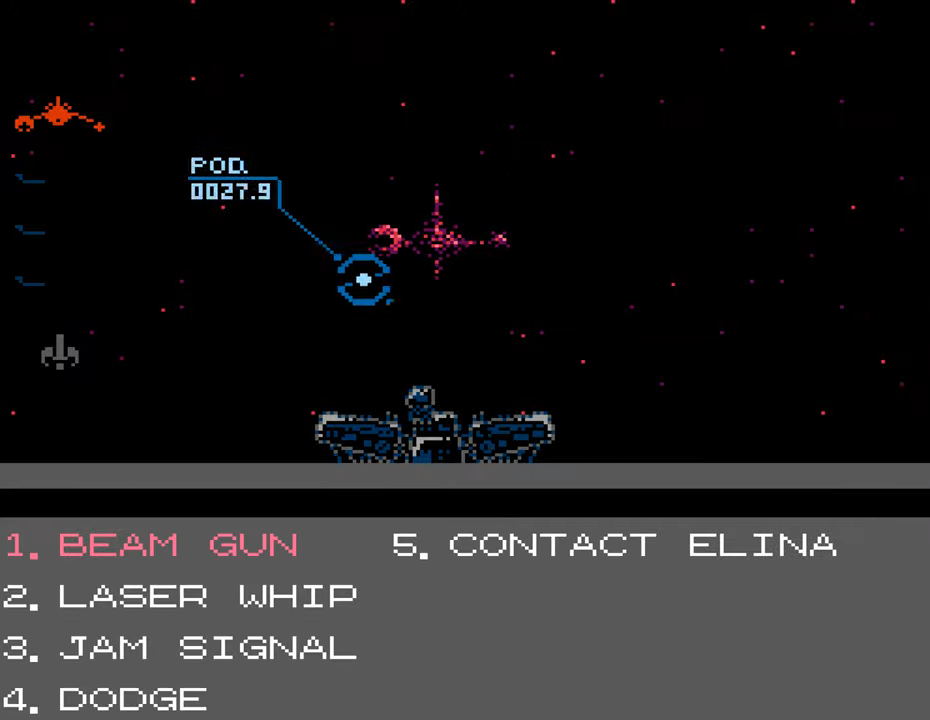

Once Azusa is freed, Tadashi, Elina, and the others must prepare for the final battle against the aliens. Here again, the climax is memorable, especially when it comes to defending the Stork space base against the invasion. The game then switches to a real-time combat system, which is once again fairly simplistic, where you have 40 seconds to make your decision in order to eliminate enemy fire and waves, each wave bringing you irrevocably closer to the end, which may seem abrupt. However, unlike other research I have done, Yoshimiru assured me that the game had only one ending and that no other ending was planned. These last few sentences suggest that the development of Metal Slader Glory encountered a few dead ends, even though it is very common for video games to have content cut from them, a constant even. But Metal Slader Glory is not like other games: more than half of its content was cut.

☆よしみる: 最後の戦闘シーンの分岐と、ゲーム全体の台詞の数がカットされています。

エンディングに分岐は無かったので、他のエンディングはありません。

Yoshimiru Hoshi : « The ramifications of the final battle scene and the number of lines of dialogue throughout the game have been reduced.

There were no ramifications in the ending, so there are no other endings. »

Evolution

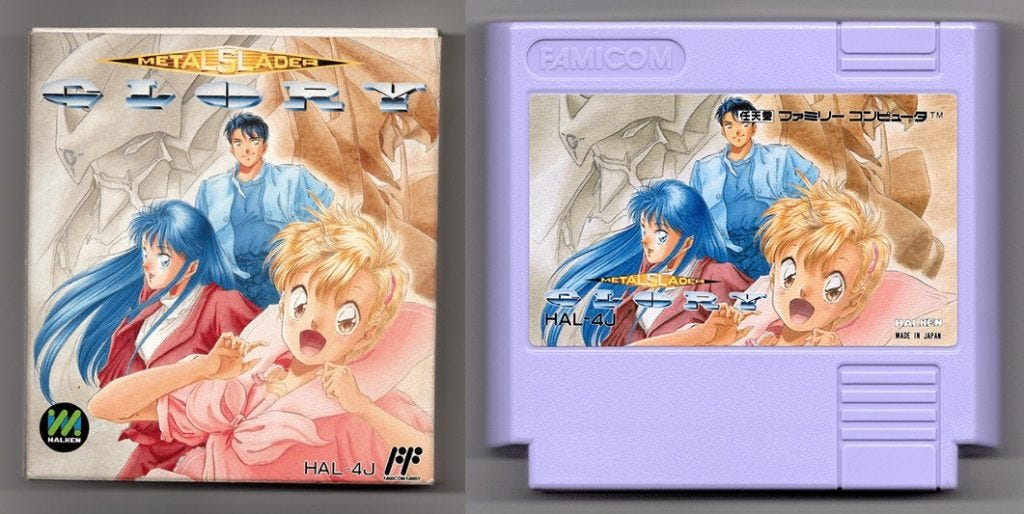

In the past, video games were created much more quickly than they are now. For many of them, it was a matter of a few weeks or months, but rarely more. Metal Slader Glory was released in 1991, after four years of development. This was a time when technology was evolving and new machines were appearing, notably the successor to the Famicom. Of those four long years, Yoshimiru spent twelve months establishing the direction of the project, its systems and its script. But nothing could compare to the problem of cartridge storage.

The storage capacity of Famicom cartridges evolved significantly between the console’s launch and its widespread adoption. In 1983, all cartridges had a capacity of 24 KB. There were some exceptions to this standard at the time, but it was shattered in 1986 when, within a few months, cartridges exceeded 48, 128 and then 256 KB, which became the average standard. This did not prevent them from having greater storage capacity on certain titles such as Dragon Quest IV with 512 KB and Kirby’s Adventure with 768 KB. Metal Slader Glory, meanwhile, reached the extraordinary size of 1 MB.

To overcome this problem, Metal Slader Glory incorporates a special chip, the MMC5. This chip is what is known as a mapper. As tech specialist Upsilandre explained to me, it is a kind of ‘switch that manipulates the cartridge port address bus to extend it virtually’. The NES (or Famicom) had seen several generations of mappers. Nintendo’s mappers (the famous MMCs) came in five versions, although the MMC3 chip was the most common. The MMC5 chip, produced at the end of the Famicom’s life, is certainly the most complex, but also the most powerful of all. It allows the use of a 512 KB graphics ROM, which made it easier to program VFX, as well as richer and more colourful image composition, one of the successes of Metal Slader Glory.

However, according to its director, the game was originally intended for the Super Famicom before HAL’s executive decision was made to release the game on its original platform. Nintendo, possibly incorporating MCC5 chips into its Super Mario Bros 3. cartridges that were to be released in Europe according to some reports, undoubtedly offered to supply HAL with them, shifting development to the other platform. Yoshimiru also revealed to me that Nintendo had offered HAL a very favourable price for the production of a specific number of chips.

☆よしみる : スーパーファミコンで発売する案もありました。

ですが、任天堂が新しい基板『MMC5』を提供してくれる事が決まり、

協議した結果、ファミコンで発売する事になりました。

私の知る話では、任天堂とハル研は特別な関係にあったため、ハル研に対して任天堂

が『MMC5』の基板を特別に安価で提供する事になり、

ファミコンで発売する方が価格を抑えられるとの事でした。

『MMC5』の基板がとても高価だったため、任天堂がハル研に安価で提供する本数が初

めから決まっていたようです。

Yoshimiru Hoshi : « We had planned to release it (Metal Slader Glory) on Super Famicom.

But Nintendo decided to provide us with a new ‘MMC5’ chip,

and after discussion, we decided to release it on Famicom.

From what I understand, Nintendo and HAL Laboratory had a special relationship, which allowed Nintendo

to supply HAL Laboratory with the MMC5 card at a particularly favourable price.

It was therefore more profitable to market it on the Famicom.

The MMC5 chip was very expensive, and it seems that the number of cartridges Nintendo

supplied to HAL Laboratory at a low price was fixed from the outset. »

ESCAPE

Despite all the production difficulties, there is still an urban legend surrounding this game: its marketing. While all sources agree that it was unreasonable, Yoshimiru refuted this, saying that it was traditional for a game in Japan. Perhaps this misconception stems from a misinterpretation of an interview with Satoru Iwata, who nevertheless described the management of the project as a ‘mistake’. However, it was Iwata who did everything in his power to ensure that the project was completed without putting any pressure on the team. He even worked on programming certain passages, although this is not mentioned in the credits.

☆よしみる: ゲーム誌の広告ページが主だったと記憶しています。

日本で言われている『マーケティングは大規模に行われた』はおそらく誤りで、

他のゲームソフトと特に変わらないマーケティングでした。

Yoshimiru Hoshi : « I remember that this (advertising) was mainly done in the advertising pages of video game magazines.

What they say in Japan, namely that ‘marketing was carried out on a large scale’, is probably false,

as the marketing was no different from that of other video games. »

☆よしみる: 制作期間がかかったため、HAL研究所内でプロジェクトが中止にならない様に支えて

くださいました。

ゲームは発売する時点で、基板の数が決まっていたため、

発売本数は決まっていたのです。

(12000~15000本と記憶しています。)

なので、成功とも失敗とも言えませんでした。

Yoshimiru Hoshi : « As production took a long time, he (Satoru Iwata) helped me ensure that the project was not cancelled within HAL Laboratory.

At the time of the game’s release, the number of cartridges was already fixed, and the number of copies to be sold was therefore determined.

(I believe there were between 12,000 and 15,000 copies.)

It could therefore not be called a success or a failure. »

These new insights therefore lead us to rethink the issue of HAL’s declaration of bankruptcy in the context of the economic crisis that hit Japan in the early 1990s. Iwata provided further answers in a number of interviews, citing ill-advised investments at the time (such as the creation of HAL America in 1989 I presume) and the pressure to produce questionable games. The result was harsh, and to avoid disappearing, HAL Laboratory found itself having to pay off a debt of 1.5 billion yen. Nintendo, its long-time ally, offered to wipe the slate clean on the condition that it become a second-party studio for them. It seems that the replacement of the much-maligned Tsuyoshi Ikeda by a new president, Satoru Iwata, was also on the table, but when the question was put to him, he remained impassive, offering only a slight smile.

However, it was he who would bring about the revival of HAL Laboratory in a relationship with Nintendo that was closer than ever. A new era that, starting in 1993, would prove fruitful with one of the last games for the NES, Kirby’s Adventure. The game achieved the feat of climbing to the top of the best-selling games chart in Japan in June 1993, three years after the release of the Super Famicom. In 1999, HAL finally paid off its debt, the one that had nearly destroyed it eight years earlier. It was then that Iwata was offered a role at Nintendo as head of corporate planning, before becoming its president in 2002 to rescue Nintendo from crisis, ending the Yamauchi dynasty that had begun in 1889. The rest, as they say, is history: between a tentative start, dazzling successes, a bitter failure and finally his demise, Iwata left no one indifferent.

Generations

However, Metal Slader Glory almost made a comeback before HAL Laboratory changed management in 1999. A sequel to the title was planned for the Nintendo 64 peripheral, the 64 DD. It was to feature the character from the first game, Yayoi Kisaragi (a waitress and double agent), in a kind of dating sim set a year before the initial events (I won’t say any more…). The game, like many others for the 64 DD, was ultimately cancelled. In 1999, Yoshimiru took another break from video games to join the many artists invited to participate in High School of Blitz, a card game featuring schoolgirls for the PlayStation (I won’t say any more about that either… ).

Perhaps this project gave him the opportunity to reminisce about the development of Metal Slader Glory, as he then suggested to Nintendo that they re-release the game in a director’s cut version available exclusively through the Nintendo Power distribution system. Ultimately, it changed very little from the original Super Famicom version, except for improved graphics, a few additions to the adventure, and music that I personally find less appealing. History will remember it as the last game to be released on the machine, like the ghost it always was. Because when we look back on HAL Laboratory, Metal Slader Glory is always mentioned. But no one really knows what it’s all about. A curiosity at best, a visual novel at worst, lost among the other titles that would bring glory to the studio.

☆よしみる: ディレクターズカット版も私が開発に関わっています。

任天堂に企画を出したのも私なので、驚きはありませんでした。

任天堂が開発に関わってくれるのであれば可能だと思います。

Yoshimiru Hoshi « I was also involved in the development of the Director’s Cut version.

As I was the one who proposed the project to Nintendo, I wasn’t surprised.

[And] I think [the return of Metal Slader Glory] is [still] possible if Nintendo participates in the development. »

And that’s such a shame because Metal Slader Glory is well worth discovering, especially since an English fan translation has recently become available. As a game, I found it quite remarkable in several respects, such as its production, its boldness and its clinical pace. But what I think makes the title so great is its heart. It’s a game made by enthusiasts, led by a highly talented director with ambitions that were almost too big for him, overwhelmed and consumed by his own project. Nothing is really certain about the future of the game, but Yoshimiru is adamant. If Nintendo wants it and participates in its development, Metal Slader Glory will return. And it would be well deserved. In the meantime, I leave you with the last words of its creator, thanking him a thousand times for the opportunity he gave me to revisit the project of his life with him.

☆よしみる: それまでには無いアドベンチャーゲームを作りたかったので、

企画も発想もシナリオも、私が自由に出来た開発環境を提供してくれた

ハル研のおかげだと思っています。

Yoshimiru Hoshi: « I wanted to create an adventure game that was different from anything that had come before,

and I think it was thanks to HAL Laboratory that I was able to benefit from a development environment

that gave me complete freedom in terms of design, ideation and storyline. »