A few weeks ago, the McLaren Formula 1 team announced a historic partnership with the fastest character in video games: Sonic. Behind this nod to history and one of the most incredible performances of the sport, this partnership could in fact be another turning point in F1’s commercial strategy: investing in the future and entertainment media. Is a future partnership between video games and F1 possible? Let’s talk about it.

Days of Thunder

It’s the 11th of April, 1993. Rain is pouring at Donington Park in England for the third round of the F1 World Championship. Alain Prost starts in pole position, followed by Damon Hill and Michael Schumacher. Ayrton Senna starts in fourth place, before dropping to fifth when the lights go out, overtaken by Karl Wendlinger. Senna then begins a legendary lap, overtaking one car after another as they struggle in the rain. No one saw the Brazilian driver again as he went on to achieve one of the most impressive victories of his career, some would say the most impressive. A victory crowned by that first lap, which was quickly named « the ‘lap of God ».

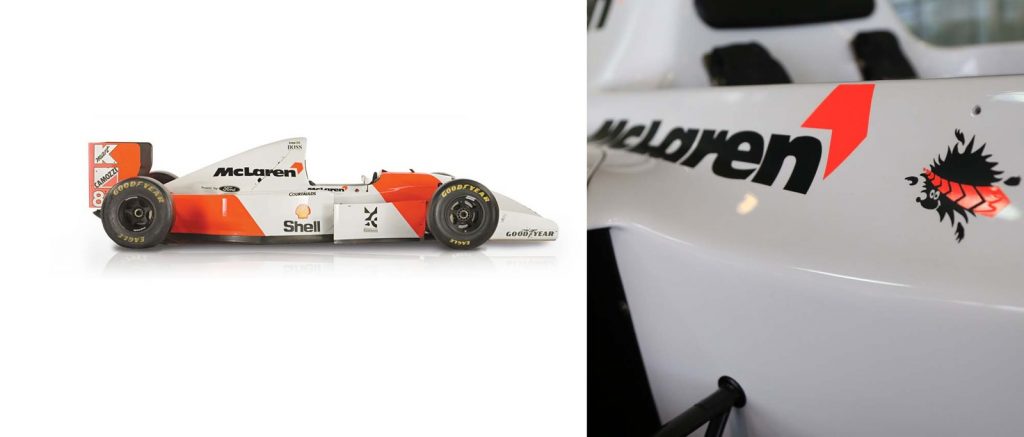

On the podium, Senna lifts the winner’s trophy alongside Alain Prost and Damon Hill. But this trophy is a bit unusual. While one might expect a cup or a bowl, this one bears the image of one of the greatest video game mascots of that time, Sonic. The hedgehog also appeared on the circuit’s advertising hoardings and even on the grid girls (the women who held up the drivers’ numbers), who were dressed in costumes featuring the Sega character. Sega was none other than the title sponsor of the Donington Grand Prix.

But that’s not all. Sega was also at the time the privileged partner of Williams Renault, the reigning world champion team, which included Alain Prost and Damon Hill in its ranks. Damon Hill owes his survival in F1 to this partnership, which was established through one of his best friends with the Sega UK marketing team led by Simon Morris. This association was only revealed during the second race of the season, at Interlagos in Brazil, Ayrton Senna’s home soil, where Sonic’s feet were visible on the sidepods of the Williams car. It almost seemed like a betrayal to Ayrton, who subsequently decided to stick what looked like a squashed hedgehog on the bodywork of his McLaren, as a reference to this sponsorship.

Over Drive

If I stick with the term « betrayal », it is because Ayrton had been the star of Super Monaco GP 2, published by Sega. This collaboration was made possible thanks to the boldness of Tectoy, a company based in Sao Paulo and the Japanese firm’s official partner for importing Sega’s consoles, particularly the Master System. More than just a licensing agreement, the Brazilian company was responsible for importing components and software and assembling them for its customers, bypassing the draconian rules surrounding the import of consoles, which was nearly impossible in Brazil in the 1980s. The Master System became a benchmark in the country, with an installed base of 80 to 85% of the total number of consoles. At the beginning of the 1990s, however, Sega had another priority: the Genesis.

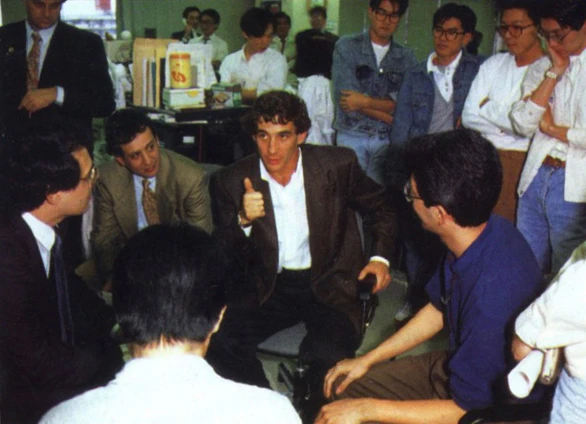

This paradigm shift meant that Tectoy had to seek out new opportunities to reinvent itself, and one of the ideas was to deal a partnership with the living legend Ayrton Senna, at the time a two-time Formula 1 world champion. Ayrton was powered by Honda, the Japanese engine manufacturer, while the last two F1 world championships in 1989 and 1990 were contested at Suzuka, Japan, between the two eternal rivals, Prost and Senna, with two legendary outcomes. And to complete the whole picture, the president of Sega, Ayao Nakayama, was friends with Shoichiro Irimajiri, the head of engine development for the McLaren Honda team. The proposal was therefore immediately accepted by the board in Tokyo. Sega now had to negotiate with the Brazilian driver, just as it had done in its policy of starification of its Genesis, notably by attracting Michael Jackson to develop the famous Moonwalker. In concrete terms, in exchange for the use of the star’s image for a nominal fee, Senna would receive royalties on each copy sold and have a say in the creation of the game bearing his image.

Ayrton was therefore tasked with bringing his experience to the development team in order to make Super Monaco GP 2 as realistic as possible. For example, modifications were made to the kerbs, which in reality make it easier for cars to turn. In a prototype version, they damaged them, which did not please Senna, who asked for the entire physics to be rebuilt. He also designed two of the circuits for the ‘Senna Grand Prix’ and provided advices on the various championship tracks, including Barcelona, which was new to the 1991 calendar. Not wanting to give impressions of a circuit he didn’t know, the Sega teams had to wait until the end of the first Barcelona Grand Prix to take Senna’s commentaries and integrate them into the final game. Senna’s final request was reportedly that the game must be ported to the Master System in order to meet Brazilian demand, but no source seems to corroborate this request, as the game appears to have been originally planned for Master System, Genesis and Game Gear.

Fast’n Furious

While Super Monaco GP 2 is a landmark title in the F1 video game ecosystem, it didn’t actually take long for games on the subject to appear. In 1976, Nakamura Manufacturing Company (later Namco) released F-1,, an electromechanical game (which could be considered the ancestor of video games), itself undoubtedly inspired by the -1969 !!- title Speedway. In 1982, Namco followed up with Pole Position, a revolutionary game that offered players the chance to take a complete lap of the Fuji circuit, which was then part of the F1 championship calendar. Behind Pole Position was actually the designer of F-1, Sho Osugi, accompanied by Kazunori Sawano and Shinichiro Okamoto. The first game officially licensed by the FIA (Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile) did not arrive until 1991 under the name F1 – Grand Prix for the Super Nintendo. Since then, almost every season has had its own official game, released by several publishers, from EA to Codemasters. But I won’t go into further detail in this analysis, as the aim is to diverge from the logic of partnerships other than this one.

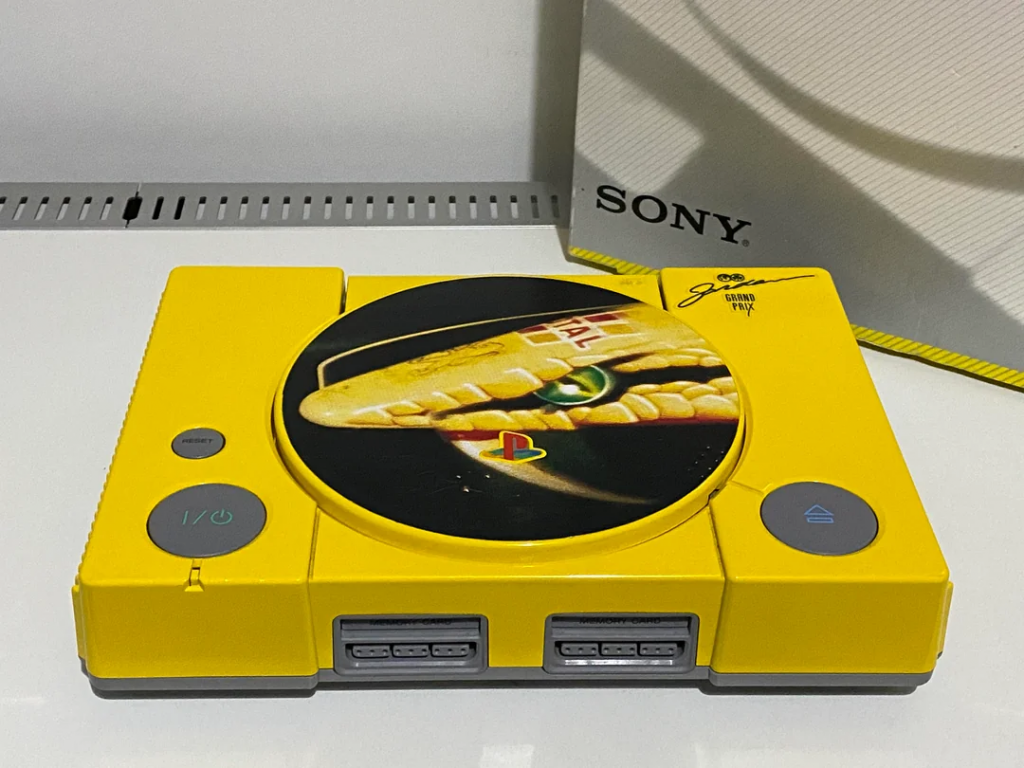

However, like Ayrton Senna, other drivers have left their name on a game title, such as Nigel Mansell (1992 world champion) and Alain Prost for Prost Grand Prix, published by Canal + Multimédia in 1998, when the French car proudly displaying the PlayStation logo. The Jordan team even made a name for itself at the time by signing an official PlayStation produced in a limited edition of only 20 copies. At the time, sponsors could be found on the bodywork but also sometimes on the helmets, the only visible part of the driver during the race. Long after Alain Prost wore Sonic during the 1993 season, Swedish driver Heikki Kovalainen presented a helmet in 2011 featuring the colours of one of the biggest video game hits of the late 2000s, Angry Birds. Rovio, the game’s developer, had decided to financially support the driver’s entire campaign, which was unfortunately struggling in a very underperforming car. Closer to out time, current McLaren driver Lando Norris stepped into the shoes of Master Chief with a helmet bearing the image of the Halo character for the 2022 Singapore Grand Prix, during a prosperous period for F1.

Miracle In Lane

Five years earlier, Formula One Management, then run by Bernie Ecclestone, was suffering from a loss of momentum due to controversial regulations and an ageing audience. Then the F1 Management came under the American banner of Liberty Media with a simple goal: to breathe new life into the sport. Liberty Media took over Grand Prix weekends and communication channels in an attempt to implement its new policy. Its most famous product, produced by Netflix, is ‘Drive to Survive’. The series boosted audience, particularly in the United States, where fans are more accustomed to Nascar and its much more unpredictable and spectacular single-seater championship, Indycar. The strategy of bringing F1 closer to the public also involves the implementation of numerous exotic and/or urban circuit projects, particularly in emerging markets.

But it is also very interesting to take a closer look at another phenomenon that started even earlier than Drive to Survive : the F1 Esports Series. Launched in 2017, this competition sees players from around the world compete virtually on official games. Although it had modest beginnings, the following year saw all F1 manufacturers commit to supporting virtual drivers (only Ferrari was missing, but they were present from 2019 onwards). Although the teams have a designated driver, they must sign another talent from among 66,000 contenders through a ‘pro draft’. The objective is simple, and identical to reality: to designate a driver champion and a constructor champion (team) at the end of the season.

With 5.5 million people watching the final race, the second season of the Esports Series was a great success. This success capitalised on a 75% increase in viewership, with an audience whose average age was under 34. The third season took a completely unexpected turn in 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic interrupted and then slowed down all international competitions. From then on, real F1 drivers and celebrities took part in frenzied (but not always very clean) races, taking esports competition into another dimension. Of all sports, F1 has benefited the most from the pandemic, especially when the major media outlets that used to broadcast it, such as Sky Sports and Canal + (the French international broadcaster for Formula 1), decided to cover the various events and even organise them, in a relative way. 2021 even was the best year in terms of audience figures for the championship, for an F1 season that would also prove to be historic, before the very satisfactory audience figures became somewhat tarnished.

That was without counting on a decision to simply cancel the event at the end of 2023 when Gfinity (which specialises more in Call of Duty competitions) and F1 decided to part ways before the start of the season. Although ESL (Electronic Sports League) would take over the organisation of the championship, renamed F1 Sim Racing, the disastrous communication surrounding the announcement of the start of the season discredited it, with players and the public turning to community events. Announced for the 24th of November, the 2023-2024 championship would not start until April, following a disagreement between F1 and ESL, according to some sources. The 2025 season started last January and ended two months later, with no broadcasting issues.

However, viewership figures remain stable compared to previous years, especially when weighted against total airtime, which reached 48 hours and 35 minutes compared to 36 hours and 15 minutes in 2022, for example. Nevertheless, F1 Sim Racing seems to be losing momentum, a decline that correlates with other esports events cancelled in previous years, combined with the difficulty of attracting a new audience to its flagship product, which remains Formula 1. Liberty Media therefore had to turn to other ideas to continue capitalising on the enthusiasm surrounding F1, even if it meant sacrificing the one that allowed it to transcend its identity, Drive to Survive, whose audiences no longer seem to be following and whose relevance is increasingly questioned each year. And you don’t need look further than the release of the film F1 with Brad Pitt to be convinced of this, with entertainment that only Hollywood can provide, to broaden its audience. In reality, F1 has already begun its transformation.

Baby Driver

At the 2025 Miami Grand Prix, drivers took part in the traditional parade. A few hours before the race, all twenty protagonists drove around the circuit to greet the crowd and answer questions from journalists. Sometimes gathered on a truck, sometimes separated in vintage cars, the drivers engaged in Miami in a frantic race at 20 km/h in cars built entirely from Lego. It was an extremely funny and refreshing sequence that further anchored the brick brand in the F1 ecosystem and cemented the partnership formed in September 2024 between Lego and Formula One Management. In May of 2025, another partnership that seemed to have nothing to do with F1 was made official: Disney. In addition to the revival of a possible F1 circuit in Marne-la-Vallée (the place of Disneyland Paris), which has so far only hosted demonstration shows (even though a real Grand Prix project was considered in the late 2000s), we can only wonder about the presence of the little mouse in the Formula 1 circus.

However, everything makes sense when you analyse the various press releases and the commercial strategy implemented by Liberty Media in recent years to promote its product. The primary objective is actually to attract young people, an audience that has long been neglected. And it’s an audience that is returning the favour, as F1 continues to reach younger fans, ‘with more than 50% of followers on TikTok and 40% of followers on Instagram under the age of 25,’ reported Emily Prazer, Chief Commercial Officer of Formula 1. This figure correlates with another equally interesting statistic reported by Tasia Fillipattos, President of Disney Consumer Product, who noted that 4 million children aged 8 to 12 regularly follow Formula 1.

The aim of these two partnerships is therefore simple: to expand the fanbase worldwide, estimated at 840 million people in May of 2025, while retaining its young consumers, who, in turn, could encourage their children to consume F1. This strategy, which some economists refer to as the ‘McDonald’s strategy’, is a bold one, as the F1 brand has never really targeted young people before. But thanks to the arrival of Esport, a children’s channel aimed at popularising F1, as well as the partnerships mentioned above, the strategy is paying off in a big way.

Could the first entertainment industry be Liberty Media’s next target ?

THE CHECKERED FLAG ?

Although F1 currently has no direct partnerships with video game developers or publishers (or almost none), some teams have already formed alliances for a single race. For example, Red Bull made 2017, 2018 and 2024 single-seaters available in The Crew 2 and The Crew Motorsport. And while the Austrian firm’s partnership with The Battle Cats at the 2022 Japanese Grand Prix did not set the world alight, Metaphor Re Fantazio’s partnership with the Haas team in September 2024 attracted much more attention. One of the game’s protagonists is named Hulkenberg, the same name as the team’s driver Nico Hulkenberg (who transferred to the Kick Sauber F1 Team at the start of the 2025 season). The character’s head was therefore placed on the front wing of the German driver’s car. Kevin Magnussen’s other car featured a sticker of another character, Strohl. An intriguing character name which, by funny coincidence, could be a reference to another Canadian driver from the Aston Martin team, Lance Stroll.

A funny coincidence that isn’t really a coincidence at all, since an insider revealed a few weeks after the game’s release that many of the characters in the game had been given preliminary names based on racing drivers. Grosjean for the former French driver Romain Grosjean, Bottas for the Finnish driver Valterri Bottas, and my favourite, Senna, in reference to Ayrton Senna, who became Louis in the final game, no doubt in reference to Sir Lewis Hamilton, a great admirer of Senna and holder of the record for seven world championship titles, tied with Michael Schumacher. This partnership is all the more amusing given that Atlus’ press release makes no mention of any connection between the name of the driver Hulkenberg and the character in the game.

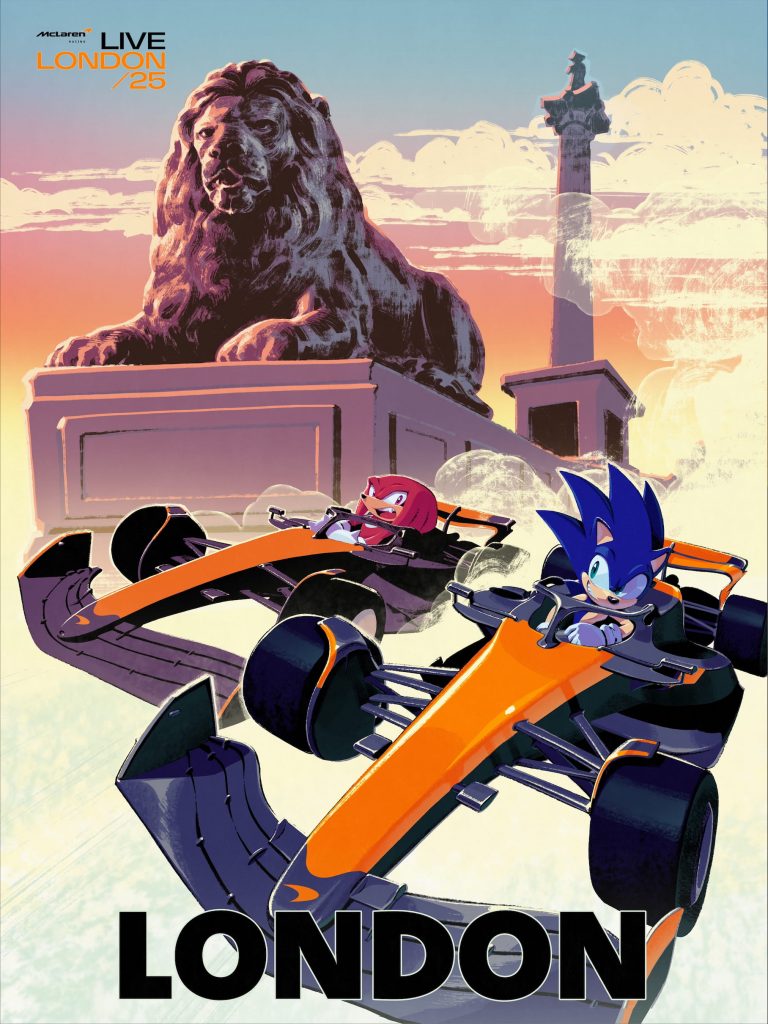

It’s only a short step from Atlus to Sega, and a few weeks ago, Sonic and McLaren officially announced their collaboration. While this collaboration builds on the story we saw earlier, it is entirely in line with F1’s policy. Louise McEwen, McLaren’ Chief Commercial Officer, welcomed the team’s openness « to a wider, younger global audience. » It could hardly be more explicit. While the notion of ’official gaming partner » is rather vague and could simply refer to Sega’s Racing Around the World event, the notion of « multi-year parternship » opens endless possibilities. The first steps of the collaboration were seen on the 2nd and 3rd of July at McLaren Racing Live in Trafalgar Square. The lucky ones were able to take part in a speed challenge organised around the release of Sonic Racing CrossWorlds to win T-shirts and an exclusive manga illustrated by Yuki Imada, the illustrator of the manga Shadow the Hedgehog. This same character, beloved by fans, whose motorbike had already been spotted in the Moto GP paddocks (the equivalent of F1 for motorbikes) in the United States and England last year, was undoubtedly there to tease the release of Sonic 3 in cinemas.

At the same time, Lando Norris and Oscar Piastri, the two McLaren drivers, got together for a promotional shoot for Sonic Racing: CrossWorlds. Promotion for the game has picked up pace recently, with influencers and journalists invited to the McLaren team’s operational base in England (the McLaren Technological Centre) to test the game in early August and discover the behind-the-scenes story of the brand. The game is still scheduled for release on the 25th of September on all platforms and will feature characters from the Sonic universe, as well as a few guests from Minecraft and Like A Dragon.

Is it possible to see Oscar and Lando in the new Sonic racing game ? We already have a precedent, which is Danica Patrick. Often mocked across the Atlantic for her questionable performances, particularly in the second half of her career, Danica remains a seasoned driver and the only woman to have won an IndyCar race and even finished on the podium of one of the most prestigious races in the world, the Indianapolis 500. She could even have joined F1if the economic situation had allowed it. At the very least, she joined the cast of Sega’s Sonic and All Stars Racing Transformed in 2012, which even used her as a selling point in a promotional trailer.

Of course, it is still too early to know whether this strategy is short, medium or long-term. As we have seen, F1 and video games have repeatedly had brief flings, without ever really bringing any major projects to fruition. Nevertheless, it’s very interesting to consider the possible genesis of a strategy that, perhaps for one of the first times, aims to integrate video games into the heart of an international audience. The only example to date in sport remains that of PlayStation, which has managed to become synonymous with the Champions League since 1997 (article in french). It remains to be seen whether the target audience will really follow the craze. It also remains to be seen whether F1, apart from coherent gaming partnerships such as that between Sonic and McLaren, will manage to find long-term interest in this strategy, particularly with the objective of attracting a young audience and then retaining it more effectively.

When contacted for more information on the overall video game strategy, neither Louise McEwen nor Emily Prazer responded to this article.

More resources :

https://www.timeextension.com/features/how-pirate-television-helped-sega-beat-nintendo-in-the-uk

https://www.thesegalounge.com/199-stefanoarnhold/

https://esportsinsider.com/2024/08/the-rise-fall-and-future-of-f1-esports